Collective Violence as Social Control: examples in Tanzania and USA.

Theory of Collective Violence as Social Control

Collective Violence as Social Control theory as described by Senechal de la Roche (1996) has been helpful in understanding the relationship between the violence witnessed at the bombing of the US Embassy in Dar es Salaam Tanzania and the ‘mob violence’ we see on the streets of Dar es Salaam, and recently witnessed at the United States Capitol in Washington DC.

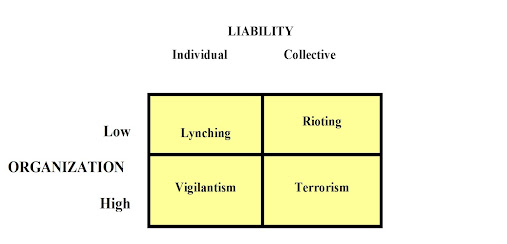

She describes the 4 types of unilateral collective violence

and categorizes them by Liability of the victims and how the event was Organized.

Unilateral collective violence in Tanzania

The violence that I witnessed at the US Embassy in 1998 is defined as Terrorism, in the above model. It was a highly organized attack – simultaneously in 3 neighboring countries. Responsibility was collective – in that anybody connected with Americans was a target; the victims included the Tanzanian guards, the Tanzanian driver of the truck bomb, and some Africa people in line for visas. No Americans were killed or severely physically injured in that incident.

Rioting has occurred in Tanzania, uncommonly, by demographically similar petty traders when police have forcibly tried to remove them from selling their wares on the street.

Most of the homicides we see in Dar es Salaam are due to lynching and vigilantism. The person who is liable/ to be held responsible is an individual. The perpetrators are targeting individual people who are going against community norms, usually stealing, but sometimes adultery or alleged witchcraft can be heavily punished as well. The lynching occurs, most commonly, when a person is caught stealing; at that time, the mob will come together spontaneously to punish the thief. In vigilantism, a chronic thief is watched and warned; if he does not stop on his own, he will be forced to by the community.

For Tanzania this gives me hope. It seems, because the liability of the victim is individual that the repercussions of petty theft, (injury or death of the thief through vigilantism or lynching), can be controlled by the victim himself for the most part. If he stops stealing, he won’t be killed by lynchers of vigilantes. The issue then becomes, how to enable the thief to rise over the many obstacles that have led him to this life of petty crime.

Unilateral collective violence at the US capitol

Events at the United States Capitol in Washington DC on 6 January 2021 contained all 4 elements of unilateral collective violence. Some people had been organizing/planning with each other and went prepared for a violent event at a collective target in the Capitol– those were terrorists. Others went to see what would happen, and were swept into violence – those were rioters.

In videos we can see a mob spontaneously descending upon a police officer; he was lynched amidst the rioting. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/11/us/capitol-mob-violence-police.html

In the New York Times video from which the above photo was taken, people are hitting the victim (unusually, a policeman) with whatever is available: sticks, a flag pole, a stolen police shield. There is no particular organization to the punishment; you can see people pushing forward in order to participate, and other people standing aside, watching, interested but not participating directly.

We also saw photos of individuals with plastic zip-ties, implying they were aiming for some individuals to be taken as hostages. These are vigilantes taking the law into their own hands.

Largely this violence against the Capital would be characterized as terrorism stirring the rioters to action.This idea of collective culpability means that everybody loses an element of safety. The perpetrators don’t need to know you to find you guilty. According to theory, Terrorism varies directly with social polarization; it needs to be addressed systemically.

Roberta Senechal de la Roche is professor emeritus at William and Lee University in West Virginia. One of her important papers is ‘Violence as Social Control.’ Sociol Forum 11, 97–128 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02408303)

Comments

Post a Comment